There are two types of people in this world when it comes to the use of light: those who want it all, and those who are wrong. Before you get upset, allow me to make my case.

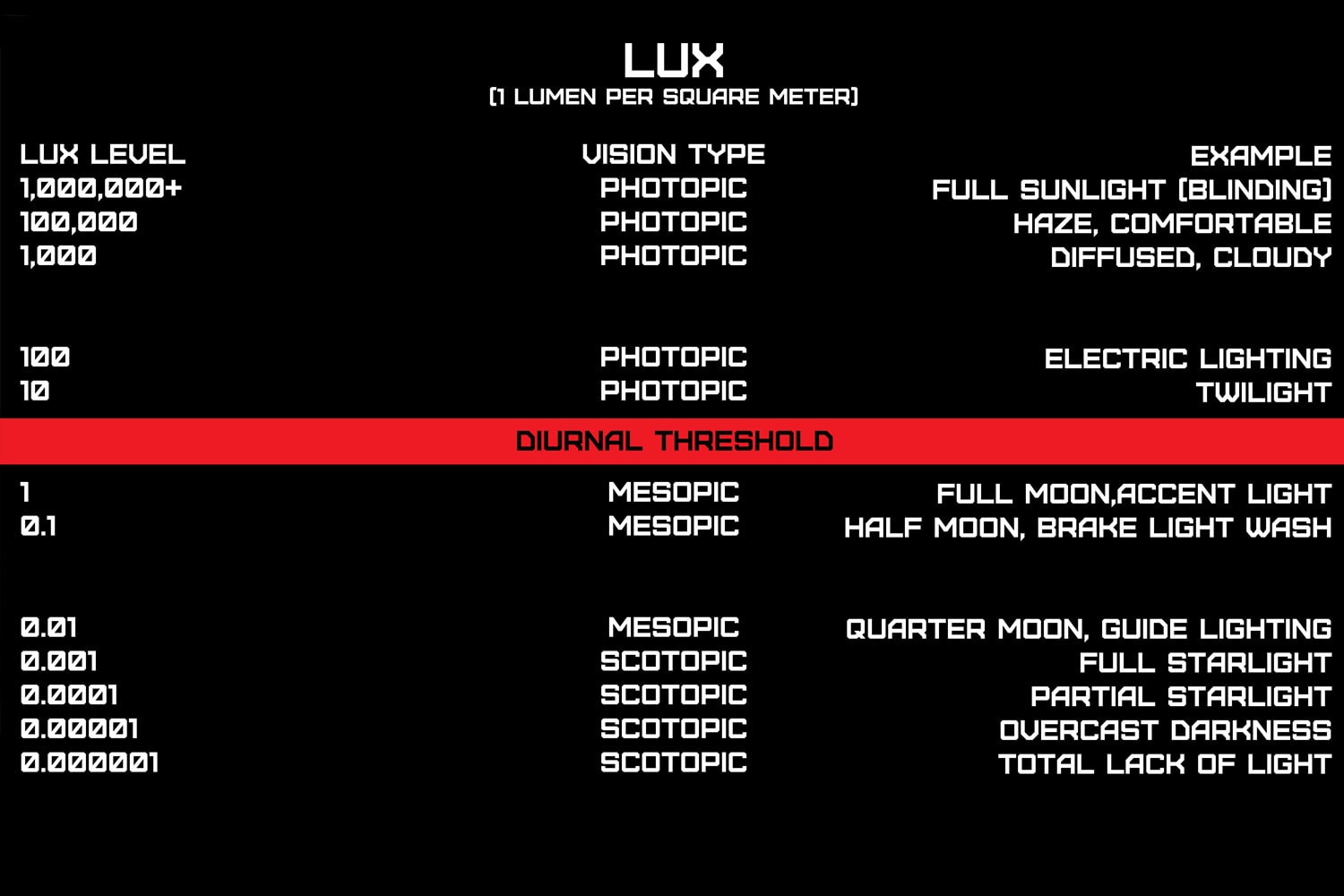

To start, let’s think about daylight. The sun, giver of all life, inspiration behind myth and machination, source of great joy and bitter annoyance (depending on which way you’re driving given a certain time of day) produces a maximum of 98,000 lux. Lux is Lumens per square meter and as most readers will know, lumen is the preferred measurement for flashlights, at least as far as marketing and appreciable metrics are concerned.

The sun provides us with the ability to gather data, it illuminates everything during the day that its light can touch, and is so bright that it can cast light into spaces that it doesn’t directly touch. Why is this relevant to a conversation about artificial light used at night or in artificial low light? Because when it’s dim we don’t have a sun, which means we don’t have the same visual advantages when it comes to gathering data. This is what it’s all about: seeing as much as you can, as soon as you can.

Lumen is a functional measure of a light’s intensity or total brightness output at a given distance, whereas candela is a measure of the intensity of the beam at a focused point. I don’t know why the majority of flashlight manufacturers decided to use lumens as opposed to candela to market their product, but it’s mostly academic because the average self-defense minded person who recognizes the need for light has a basic appreciation for the difference between lumen levels (at least in a gross fashion).

So, as a layman, I can tell the difference between 250 lumens and 500 lumens, especially if I see both used at the same time.

Why are lumens important? How many do we need? Is there a number that is enough? Hopefully I can answer each and every one of those questions. Not to be too pedantic, but first let’s look at just what low light is. To do that, we use Lux.

Photopic light is daylight, or artificial light that allows for full color vision and discernable perception of contrast and hue.

The diurnal threshold is the photonic barrier between full color vision and the beginning of vision degradation. This is where the commonly understood low light begins.

Mesopic light is twilight, the sun has recently set or the artificial lighting is dim. Your average low pressure sodium street light provides a high mesopic light. Hue and contrast are affected; flashlights do not increase outdoor light to an appreciable level.

Scotopic light is darkness, when the sun has been set for an hour or more or there is no proximate artificial light. When the eye can no longer perceive color is the best way to measure when scotopic light begins.

You are a diurnal predator and the diurnal threshold is where we begin to appreciate artificial light. This is our evolution. Our eyes, the single biggest source of actionable data, really suck in dim light. In fact, our vision in dim light is so bad that even with fully adjusted eyes in darkness, the best vision we can hope for is 20/180 (legal blindness is 20/200). If that was the only problem it wouldn’t be so bad, but the eye when going from light to dark can be as bad as 20/800 until adaptation occurs, which as I’m sure you have heard, takes twenty to forty minutes (useful adaptation varies from person to person and situation to situation). Color vision is lost and the only real advantage given is a perceived increase in the ability to track movement.

The human eye lacks a Tapetum Lucidum, which is a layer of tissue behind the retina in the eye of many vertebrates that reflects visible light back through the retina to increase the amount of light available to the photoreceptors. Cats have it, dogs have it, we don’t. But we have thumbs and have been to the moon, so it all works out.

Because we generally suck at seeing in the dark, and since we have gone to great lengths to increase the amount of darkness we can be in at any given time (houses, commercial buildings, parking garages, subways, double-wide trailers like the one that houses Nancy’s Squat’n’Gobble, and other tributes to our urban sprawl) we need artificial light, and not all artificial light is created equal.

When it comes to using light for offensive and defensive purposes, we want all the light we can get. Some disagree; I know, I used to be one of them (and so was Merrill).

So why two schools of thought? Why is there a “just enough” camp and an “all you can have” camp? I’m sure that would be a completely separate article topic that would focus on the evolution of low light training. This isn’t that article; instead we’ll just identify what each side of the debate wants and why.

The “just enough light” camp believes lights should have a maximum brightness either directly related to where the light is most likely to be used or overall no matter its environment of use.

Generally it’s understood that using a powerful light incorrectly can hinder the vision of the shooter. Light can reflect off walls, mirrors, cover, or any other manner of surfaces, and this light will blind or disorient the shooter. Having seen many a shooter new to low light experience this issue, both on square ranges and in shoot houses (not to mention in the real world), there is some merit to this camp. Of course the merit lies totally in a lack of proper training and presupposing that the just enough light is actually going to be enough. I used to believe in this.

A few experiences when just “enough” was not, and a more critical understanding of how to teach spatial awareness changed my mind forever. We’ll get to that.

The “all the lumens” camp is just that: they believe you should have as much light as possible. It’s a beautifully simplistic idea that requires very little additional training over the just enough basics. The light must be as bright as possible, and all potential negatives are overcome with training.

The reason you want as much light as possible is because you don’t know in what situation you’ll need the light. Light is needed to do two things, and it must always do them well.

Data and Control

Vision is our main source of data in a self-defense situation; the faster you get data and the better quality that data is, the faster we can make decisions. The quality of data in a low light situation is based on how much light is available in that specific location and situation, and by how much light we bring with us.

Since we have little to no control over the specific environment, we must exert maximum control over how much light we bring with us. The greater the distance to what we need to see, the more light we may need. I have no crystal ball, I don’t know at what distance I may need to illuminate a potential threat, but I do know that the more lumens I can put in front of me, the sooner I get that data and the further away from the person or object I can get it.

Having enough light may be the difference between deterring a potential threat at distance and having to identify it up close.

Light also provides control. By pushing the hot spot of a light into a threat or potential threats face, I can remove their visual horizon and control anything they see in my direction, provided the light is bright enough. The brighter the light, the further I can be from the threat and exert control. A 100 lumen light may be sufficient in an enclosed space such as a living room or hallway, but its usefulness can suffer quickly in a parking lot.

The environment controls the usefulness of the light, but so does the situation in which it must be used. It’s far more likely for me to use a light for administrative tasks than it is for shooting, but a light provides a great degree of deterrence and it allows me to get data fast.

If you believe that a 250 lumen light is enough then I challenge you to test that theory in a non-static environment, because if you’ve shot in a low light class, that class may have done you wrong.

Maximum darkness allows for maximum performance of all lights. Maximum darkness is the most common environment I’ve seen in low light training, which is great for learning the basics but terrible for teaching common sense reality. Low light classes are rife with training artificialities that build false confidence in substandard lights.

How often do you see a line of 12 or more students all running their lights at the same time? Sure that makes sense for some techniques, but if it’s the entire class, you aren’t getting actual low light training. How many low light classes require you to overcome a back lit threat, or deal with glancing light, or photonic barriers created by other lights?

Do you confront headlights, reflective surfaces, or environments in which photopic, mesopic and scotopic light all exist in close quarters to each other? All of these problems are why we need the most light we can get, because it’s unlikely the environment you’re in will be totally devoid of light (especially in urban areas) and the more ambient light present, the more light you’ll need to exert control.

If your potential threat lies across a (photonic) light barrier (such as just outside a street lamp or other source of light) the more powerful your light will need to be to defeat that light barrier and give you that data.

Inside the beam, I want maximum control and sufficient reach. Outside the beam is where no data or very little data is likely to exist, and this is the primary reason we want the most light possible. As distance increases, the more important this becomes.

If I could hold portable daylight in my hands and direct it at will in the darkness, I would. The only real potential drawbacks to the use of maximum light are all training related. The most common concern is that of blinding oneself when using a bright light in close quarters, which is entirely possible if you don’t apply general common sense to the problem. A light beam has a hot spot and a corona.

The hot spot is used for directing the most light at a single point of interest; the corona provides a less bright wash of light. When the light isn’t needed for control of direct illumination, it can (and should) be angled in such a way to provide wash or “splash” illumination without risking the hot spot reflecting off surfaces or cover back into the shooters eyes. Both Umbrella and Baseboard lighting techniques allow you to use the brightest light possible without blinding yourself. Handheld or weapon mounted, it’s too easy to off-angle a light and prevent blinding yourself. Really, really easy. Since you have spatial awareness, or are likely to use the light in an environment you are familiar with, not blinding yourself with a light that’s “too bright” is as simple as proper training and proper practice.

This may seem complicated, but it really isn’t. Take your preferred light and a friend and practice indoors, outdoors and at varied realistic distances to see if your light is giving you the data and control you want.

If it’s not bright enough to perform in varied environments at reasonable distances, then it’s time for a brighter light. Of course some people still feel like you can’t have a high output light indoors, and those people are wrong. Using the light in an off-angle method such as Umbrella or Baseboard, even in the largest of settings, will give you a greater appreciation for all the lumens, because when it comes time to use light, the light needs to give you what the sun does, and that’s all the data wherever you look.

Any argument for “just enough” is inaccurate in light (no pun intended) of proper training and proper practice.

Train Accordingly.

SureFire does not subscribe to or recommend any Techniques, Tactics & Procedures discussed by instructors referenced. SureFire is a manufacturer of the finest tactical products on the planet, and leaves it to the professionals to decide how best to implement them.